5. Large Language Models#

Taught by: Dat Doan, Alex Ganose

Getting started#

Welcome to the fifth practical session! This notebook should be run locally or on Google Colab - this can be achieved by clicking the rocket icon on the top right and selecting Colab.

Installation#

If you’re running this locally or on Colab, you’ll need to install the following packages:

pip install transformers[torch] datasets accelerate sentencepiece rdkit

Outline#

This workshop will cover the following content:

Brief recap on LLMs

Introduction to tokenisation

Generating text and the concept of temperature

Fine-tuning on a custom dataset

Pretrained chemistry language models

What are Large Language Models?#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are neural networks trained on vast amounts of text data to understand and generate human-like text. They have revolutionized natural language processing and found applications across many domains, including chemistry.

A brief history:

2017: Introduction of the Transformer architecture in “Attention is All You Need” by Vaswani et al.

2018: BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) by Google

2018: GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) by OpenAI

2019: GPT-2 demonstrates impressive text generation capabilities

2020: GPT-3 shows emergence of in-context learning with 175 billion parameters

2022: ChatGPT brings LLMs to mainstream attention

2023: Explosion of open-source models (LLaMA, Mistral, etc.)

Key concepts:

Pre-training: Models are trained on large text corpora to learn language patterns

Fine-tuning: Models are adapted to specific tasks with smaller, task-specific datasets

Transformers: The underlying architecture based on self-attention mechanisms

Autoregressive generation: Models predict the next token based on previous tokens

Applications in chemistry:

Molecule generation and design

Retrosynthesis prediction

Property prediction from molecular descriptions

Literature mining and knowledge extraction

Chemical reaction prediction

Tokenisation#

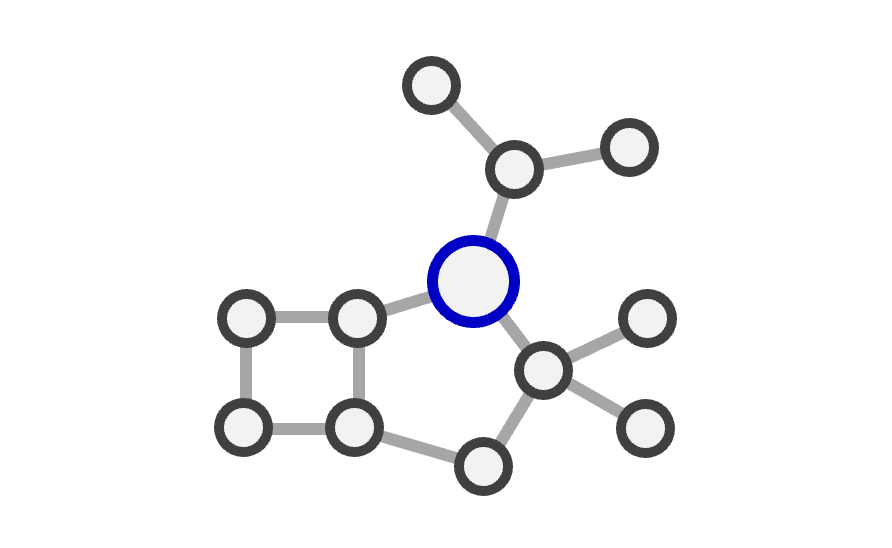

Before a language model can process text, it must be converted into numerical representations. This process is called tokenisation. Tokens are the basic units that a model works with - they could be words, subwords, or even individual characters.

Why not just use words?

Limited vocabulary: Using whole words would require an enormous vocabulary

Unknown words: New or rare words wouldn’t be in the vocabulary

Efficiency: Subword tokenisation provides a good balance

Common tokenisation methods:

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE): Iteratively merges the most frequent character pairs

WordPiece: Similar to BPE but used by BERT

SentencePiece: Language-independent tokenisation

Let’s explore tokenisation using the Hugging Face transformers library.

We’ll use a pre-trained tokenizer for distilgpt2.

This is a smaller version of GPT-2, designed to be more efficient while retaining much of the original model’s capabilities.

This tokenizer uses Byte-Pair Encoding to split text into subword tokens. It has a vocabulary size of 50,257 tokens.

# Run this cell if using Google Colab or locally with a fresh environment

! pip install transformers[torch] datasets accelerate sentencepiece rdkit

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

# Print a few tokens and their indexes from the tokenizer's vocabulary

for i, (token, index) in enumerate(tokenizer.vocab.items()):

print(f"Token: {token}, Index: {index}")

if i >= 10:

break

We can use the tokenizer to convert text into tokens:

text = "The benzene molecule has a hexagonal structure with alternating double bonds."

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text)

print("Tokens:", tokens)

print("Number of tokens:", len(tokens))

Notice how some words are split into multiple tokens (like “benzene” → “benz”, “ene”). This is subword tokenisation in action.

We can also convert tokens to their numerical IDs:

# Convert tokens to IDs

token_ids = tokenizer.encode(text)

print("Token IDs:", token_ids)

# Convert IDs back to text

decoded_text = tokenizer.decode(token_ids)

print("Decoded text:", decoded_text)

In class challenge 1#

Try tokenising different types of text and observe how the tokenizer handles them:

A simple sentence

A SMILES string (e.g., “CCO” for ethanol)

Chemical nomenclature

Text with special characters

Do the tokens make sense in a chemical context? Can you think of ways that the tokenisers could be improved for chemical problems?

examples = [

"Put your examples here...",

]

for text in examples:

# Tokenize each example and print the results

pass

Answer

for text in examples:

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text)

print(f"Text: {text}")

print(f"Tokens: {tokens}")

print(f"Number of tokens: {len(tokens)}")

print()

Notice how SMILES strings and chemical nomenclature are often split into many tokens because they weren’t common in the training data.

Generating Text with LLMs#

Now let’s load a small language model and generate some text. We’ll use the distilgpt2 model again from Hugging Face’s transformers library to keep things efficient.

First lets initialise the model and check the number of parameters.

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

print(f"Number of parameters: {sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters()):,}")

Despite being a small model, it still has 82 million parameters. However, it is much more manageable than larger models like GPT-3 or GPT-4, which have billions of parameters.

To generate text, we need to go through the following process:

Tokenize the input prompt to convert it into token IDs.

Feed the token IDs into the model to get output logits.

Sample from the output logits to generate new token IDs.

Decode the generated token IDs back into text.

Let’s now do steps 1-3:

prompt = "Chemistry is the study of"

# Encode the prompt

inputs = tokenizer.encode(prompt, return_tensors="pt")

# Generate the next tokens

outputs = model.generate(

inputs,

max_length=50,

temperature=1.0,

)

outputs

Currently, the generated output is in token IDs. Let’s decode it back to text:

generated_text = tokenizer.decode(outputs[0]).strip()

print(generated_text)

This manual approach of tokenisation, generation, and decoding is quite tiresome. We can simplify this using the pipeline API from the transformers library.

from transformers import pipeline

text_generator = pipeline("text-generation", model="distilgpt2", framework="pt")

generated = text_generator(prompt, max_new_tokens=50, temperature=1.0)

print(generated[0]['generated_text'].strip())

Understanding Temperature#

Temperature is a crucial parameter in text generation. It controls the randomness of predictions:

Low temperature (e.g., 0.1-0.5): More deterministic, picks high-probability tokens

Temperature = 1.0: Uses the model’s original probability distribution

High temperature (e.g., 1.5-2.0): More random, explores unlikely options

Mathematically, temperature modifies the softmax function used to convert logits to probabilities:

where \(z_i\) are the logits and \(T\) is the temperature.

Let’s see how temperature affects generation:

temperatures = [0.3, 1.0, 1.5]

for temp in temperatures:

print(f"\nTemperature: {temp}\n----------------")

for i in range(3):

text = text_generator(prompt, max_new_tokens=50, temperature=temp)[0]['generated_text'].strip()

print(f"Sample {i+1}: {text}\n")

Understanding beam search#

Beam search is a decoding algorithm used in sequence generation tasks, such as text generation with language models. Unlike greedy decoding, which selects the most probable token at each step, beam search maintains multiple candidate sequences (beams) at each time step. This allows the model to explore a wider range of possible outputs and can lead to more coherent and contextually relevant text generation.

At each time step, beam search expands each of the current beams by generating all possible next tokens. The algorithm then selects the top ‘k’ beams based on their cumulative probabilities, where ‘k’ is the beam width. The process continues until a stopping criterion is met, such as reaching a maximum sequence length or generating an end-of-sequence token.

We can control the beam width using the num_beams parameter in the generation method.

beams = [1, 5, 10]

for beam in beams:

print(f"\nBeam Width: {beam}\n----------------")

generated = text_generator(prompt, max_new_tokens=50, num_beams=beam)

print(generated[0]['generated_text'].strip())

In class challenge 2#

Clearly the distilgpt2 model is quite small and limited in its capabilities. Try swapping it out for other models available on the Hugging Face Model Hub, such as “gpt2”, “gpt2-medium”, or “EleutherAI/gpt-neo-125M”. How do the results differ?

You can find a list of available models here. Note that larger models will require more computational resources.

# 3, 2, 1, code!

Answer

models = ["distilgpt2", "gpt2", "gpt2-medium", "EleutherAI/gpt-neo-125M"]

for model in models:

text_generator = pipeline("text-generation", model=model, framework="pt")

generated = text_generator(prompt, max_new_tokens=50, temperature=1.0)

print(f"\nModel: {model}\n----------------")

print(generated[0]['generated_text'].strip())

Fine-tuning on a Custom Dataset#

While pre-trained models have general knowledge, they often need to be adapted to specific domains. Fine-tuning allows us to specialize a model for chemistry-related tasks.

We’ll create a simple dataset of chemistry facts and fine-tune our model on it.

Creating a Dataset#

from datasets import Dataset

chemistry_texts = [

"Water has the chemical formula H2O and consists of two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom.",

"The periodic table organizes elements by atomic number and chemical properties.",

"Sodium chloride, or table salt, has the formula NaCl and forms an ionic crystal structure.",

"Benzene is an aromatic hydrocarbon with the formula C6H6 and a hexagonal ring structure.",

"The Haber process synthesizes ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen using an iron catalyst.",

"DNA consists of four nucleotide bases: adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine.",

"Carbon dioxide has the formula CO2 and is produced during combustion and respiration.",

"The pH scale measures the acidity or basicity of a solution from 0 to 14.",

"Ethanol, with formula C2H5OH, is a common alcohol used in beverages and as a fuel.",

"Photosynthesis converts carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen using sunlight.",

]

dataset = Dataset.from_dict({"text": chemistry_texts})

print(f"Dataset size: {len(dataset)} examples")

Preparing the Data for Training#

We need to tokenize our dataset:

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

tokenizer.pad_token = tokenizer.eos_token

def tokenize_function(examples):

outputs = tokenizer(

examples["text"],

truncation=True,

max_length=128,

padding="max_length"

)

# For causal language modeling, labels are the same as input_ids

outputs["labels"] = outputs["input_ids"].copy()

return outputs

# Tokenize the dataset

tokenized_dataset = dataset.map(tokenize_function, batched=True, remove_columns=["text"])

print("Dataset tokenized successfully")

Training the Model#

Now we’ll fine-tune the model. We’ll use the Hugging Face Trainer class which handles the training loop for us:

from transformers import Trainer, TrainingArguments

# Set padding token (GPT-2 doesn't have one by default)

model.config.pad_token_id = model.config.eos_token_id

# Define training arguments

training_args = TrainingArguments(

output_dir="./chemistry_model",

num_train_epochs=5,

logging_steps=1,

learning_rate=5e-5,

weight_decay=0.01,

report_to="none" # disable wandb logging

)

# Create trainer

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

args=training_args,

train_dataset=tokenized_dataset,

)

# Train the model

trainer.train()

Testing the Fine-tuned Model#

Let’s see how the fine-tuned model performs:

prompts = [

"Water has the chemical formula",

"Benzene is an aromatic",

"The pH scale measures",

]

print("Fine-tuned model outputs:\n")

for prompt in prompts:

text_generator = pipeline("text-generation", model=model, tokenizer=tokenizer, framework="pt")

generated = text_generator(prompt, max_new_tokens=50, temperature=1.0)

output = generated[0]['generated_text'].strip()

print(f"Prompt: {prompt}\n")

print(f"Output: {output}\n")

Clearly fine-tuning has not helped much! More training data and larger models are needed for better results.

Using pre-trained chemistry models#

So far, we’ve been using general-purpose language models. However, there are models pre-trained specifically on chemistry data, such as MolT5. MolT5 was trained on a large dataset of SMILES strings paired with their corresponding chemical captions. This dataset includes a wide variety of chemical compounds, allowing the model to learn the relationships between molecular structures and their textual descriptions.

MolT5 uses the T5 architecture, which is designed for text-to-text tasks. This means that both the input (SMILES strings) and output (chemical captions) are treated as text sequences. After pre-training on the large dataset, MolT5 can be fine-tuned on specific tasks, such as generating captions for new molecules or predicting molecular properties.

Below is an example of using a pre-trained MolT5 model to generate a chemical caption from a SMILES string. MolT5 can be used using the same transformer pipeline API as before.

from transformers import T5Tokenizer, T5ForConditionalGeneration

tokenizer = T5Tokenizer.from_pretrained("laituan245/molt5-small-smiles2caption", model_max_length=512)

model = T5ForConditionalGeneration.from_pretrained('laituan245/molt5-small-smiles2caption')

MolT5 includes it’s own tokenizer customised for chemistry. Let’s tokenize a SMILES string and see how this compares to the gpt2 tokenizer we used before.

First let’s define a molecule via smiles.

from rdkit.Chem import MolFromSmiles

smiles = 'C1=CC2=C(C(=C1)[O-])NC(=CC2=O)C(=O)O'

mol = MolFromSmiles(smiles)

mol

Next, let’s tokenize the SMILES.

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(smiles)

print("MolT5 Tokens:", tokens)

print("Number of tokens:", len(tokens))

gpt2_tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("distilgpt2")

gpt2_tokens = gpt2_tokenizer.tokenize(smiles)

print("\nGPT-2 Tokens:", gpt2_tokens)

print("Number of tokens:", len(gpt2_tokens))

The tokens look quite similar. There are a few differences related to how each tokenizer handles the beginning of a sequence and how splitting is done at brackets.

Finally, we can use MolT5 to generate a caption from the smiles string.

input_ids = tokenizer(smiles, return_tensors="pt").input_ids

outputs = model.generate(input_ids, num_beams=5, max_length=512)

print(tokenizer.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True))

MolT5 also includes a model for generating smiles from a caption. We can download and run this model using the transformers library. In this case, we will use the small version of the model due to computational limitations, but medium and large versions are also available.

tokenizer = T5Tokenizer.from_pretrained("laituan245/molt5-small-caption2smiles", model_max_length=512)

model = T5ForConditionalGeneration.from_pretrained('laituan245/molt5-small-caption2smiles')

Once the model is loaded, we can create a caption and generate a SMILES string from it.

input_text = 'The molecule is a monomethoxybenzene that is 2-methoxyphenol substituted by a hydroxymethyl group at position 4. It has a role as a plant metabolite. It is a member of guaiacols and a member of benzyl alcohols.'

input_ids = tokenizer(input_text, return_tensors="pt").input_ids

outputs = model.generate(input_ids, num_beams=5, max_length=512)

generated_smiles = tokenizer.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True)

print(generated_smiles)

Let’s see what this molecule looks like using rdkit. Does it match the description?

mol = MolFromSmiles(generated_smiles)

mol

In class challenge 3#

Now it’s your turn! Try providing your own chemical description to the model and see what SMILES it generates. Does the generated molecule match your description? For example, if you describe a well known molecule for a certain function, does the model generate the correct SMILES?

# 3, 2, 1, code!

Limitations and considerations#

Important notes about LLMs for Chemistry:

Small datasets: Many of our toy datasets are far too small for real predictions

Model size: DistilGPT-2 is very small; larger models would perform better

Chemical validity: The model doesn’t know chemistry rules and may generate invalid SMILES. This must be checked as a postprocessing step.

Real applications: Production systems use:

Much larger datasets (e.g., USPTO reaction database with millions of reactions)

Specialized architectures (e.g., Molecular Transformer)

Post-processing to ensure chemical validity

Beam search for multiple predictions

Real-world models for chemistry:

Molecular Transformer: Specialized for reaction prediction

ChemGPT: Language model trained on chemical literature

Graph neural networks: Often more effective for molecular property prediction

Next steps#

Well done for completing the final workshop of the Data Analytics for Chemistry course. You have learned how a variety of supervised and unsupervised machine learning approaches can be used for chemistry problems.

The next stage is applying these techniques to a real-world chemistry dataset. You have each been assigned a dataset from the MatBench leaderboard. For the remaining time of the workshop, you should explore the features of the dataset.

More information is provided here.